Dionysus stands as one of the most fascinating and complex deities in Greek mythology. Unlike the orderly Olympians, he embodied life’s striking contrasts: ecstatic joy alongside terrifying rage, civilization against wilderness, and rigid control versus complete liberation. Born twice and raised in secrecy, this god of wine, fertility, and altered consciousness would become central to some of Greece’s most important cultural developments, including the birth of theatre itself.

His worship inspired both structured artistic performances and wild, uninhibited rituals where participants achieved transcendent states. Through his myths and festivals, the ancient Greeks explored the boundaries between the rational and irrational, the civilized and primal aspects of human nature. This enduring tension continues to influence our understanding of art, psychology, and spirituality today.

The Paradoxical Origins of Dionysus

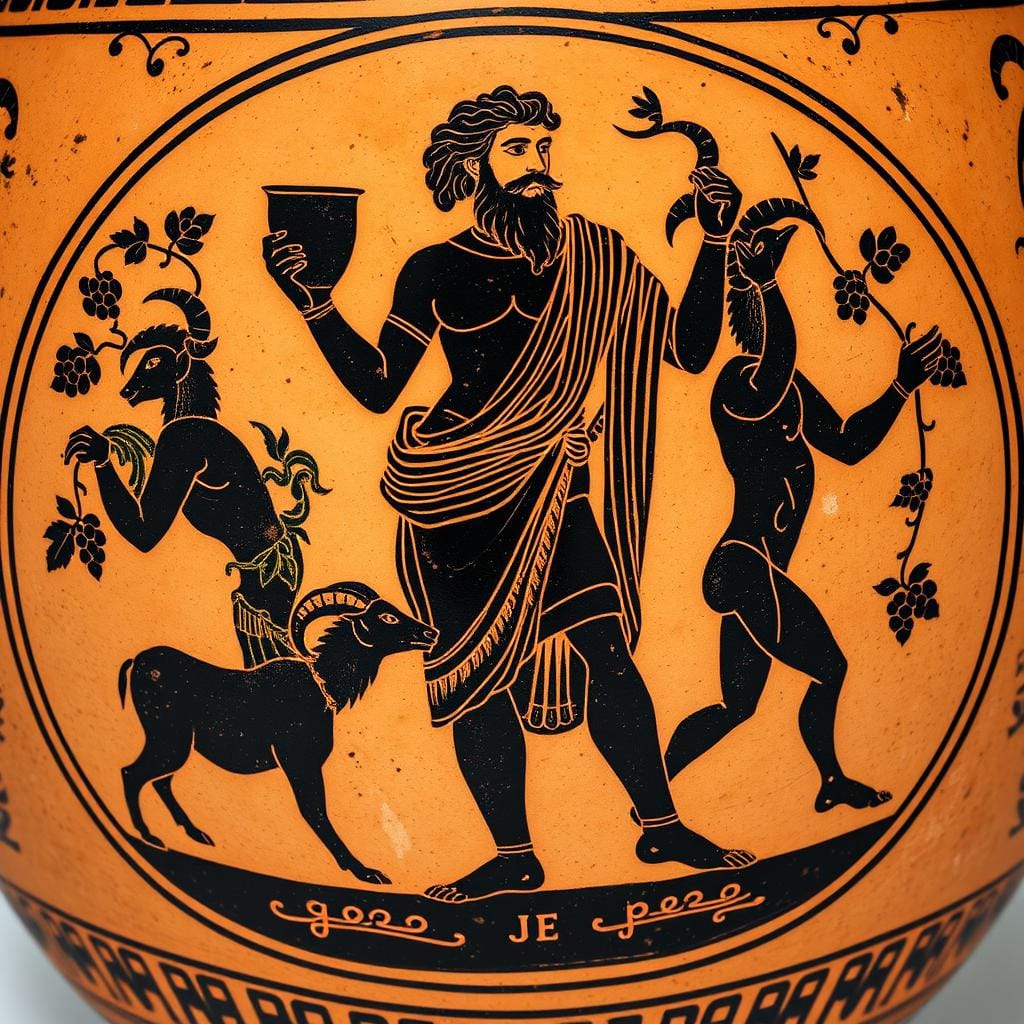

Dionysus depicted on ancient Greek pottery with his symbols of wine, ecstasy, and theatrical elements

The Twice-Born God

The most famous birth story of Dionysus reveals his unique status among the gods. He was the son of Zeus, king of the gods, and Semele, a mortal princess of Thebes. Zeus’s jealous wife, Hera, tricked the pregnant Semele into asking Zeus to reveal his true divine form. When Zeus reluctantly complied with his oath, Semele was consumed by his thunderbolts. Acting quickly, Zeus rescued their unborn child by sewing the fetal Dionysus into his own thigh until the baby was ready to be born.

This extraordinary origin earned Dionysus the epithet “twice-born” (Dimetor) and marked him as a liminal figure – neither fully divine nor mortal, but existing at the threshold between worlds. After his second birth from Zeus’s thigh, the infant Dionysus was entrusted to nymphs on the mythical Mount Nysa, further emphasizing his connection to wild, mysterious places beyond civilization.

The Orphic Mystery: Zagreus

A second, more esoteric origin story comes from the Orphic tradition. In this version, Dionysus was first born as Zagreus, son of Zeus and Persephone, queen of the underworld. The jealous Titans, encouraged by Hera, dismembered and devoured the infant Zagreus. However, Athena rescued his heart, which Zeus used to bring him back to life through Semele.

This Orphic tale of dismemberment and rebirth adds profound depth to Dionysus’s character. It connects him to ancient sacrifice rituals and the cyclical nature of life, death, and renewal. His association with Persephone further strengthens his role as a mediator between the living and the dead, the earthly and the divine.

Sacred Symbols of Dionysus

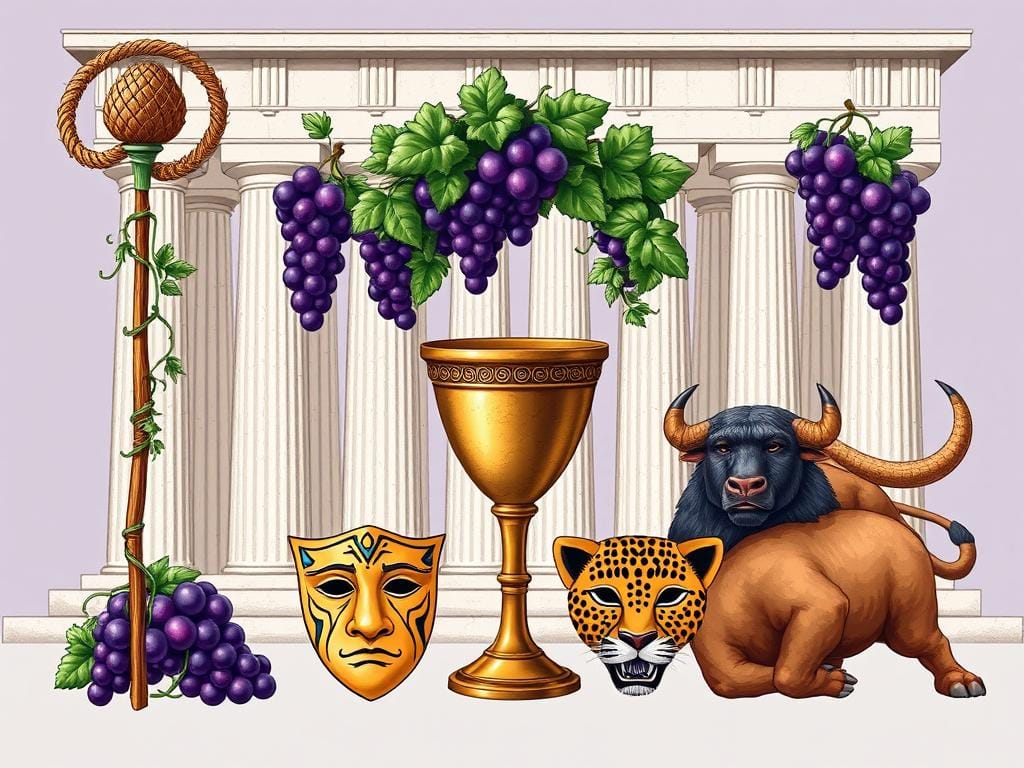

The sacred symbols of Dionysus representing his domains of influence

Dionysus was associated with a rich array of symbols that revealed his complex nature and spheres of influence. These emblems appeared frequently in art, ritual objects, and festival decorations throughout the ancient Greek world.

The Thyrsus: Divine Staff of Power

The thyrsus was Dionysus’s most distinctive attribute – a staff made from a giant fennel stalk (narthex), topped with a pine cone and wrapped with ivy vines. This sacred wand represented fertility, prosperity, and divine power. In the hands of Dionysus or his followers, it could bestow blessings or serve as a weapon against those who opposed the god. The pine cone tip symbolized fertility and immortality, while the hollow fennel stem recalled the myth of Prometheus hiding fire within fennel to give to humanity.

Grapevine and Wine: Transformation

The grapevine and wine were central to Dionysus’s identity as the discoverer of viticulture. These symbols represented cultivation, transformation, and the dual nature of wine itself – capable of inspiring both joy and madness. The process of winemaking mirrored Dionysus’s own death and rebirth in Orphic mythology, as grapes are crushed only to be transformed into something new and powerful. The kantharos, a special two-handled drinking cup, was often depicted in his hands as a direct emblem of wine’s ritual importance.

Sacred Animals: Wild Power

Several animals were sacred to Dionysus, each reflecting aspects of his nature. The bull symbolized his raw power and fertility, sometimes appearing as the god himself in certain rituals. The panther or leopard represented his connection to wild, untamed nature and exotic lands. Often shown pulling his chariot or accompanying him, these big cats emphasized his mastery over dangerous forces. Snakes, associated with rebirth through shedding their skin, appeared in Dionysian rituals as symbols of regeneration and chthonic (underworld) power.

Theatre Masks: Transformation and Performance

As god of the theatre, Dionysus was closely associated with theatrical masks representing tragedy and comedy. These masks symbolized transformation, the ability to assume different identities, and the range of human emotions from profound sorrow to ecstatic joy. The theatrical tradition that emerged from Dionysian worship explored the human condition through performance, allowing both actors and audience to temporarily step outside themselves and experience catharsis through dramatic storytelling.

| Symbol | Representation | Significance |

| Thyrsus | Fennel staff with pine cone tip wrapped in ivy | Divine power, fertility, transformation, blessing or punishment |

| Grapevine & Wine | Cultivated vine, wine cup (kantharos) | Transformation, joy/madness duality, social bonding, divine inspiration |

| Ivy | Evergreen climbing plant | Immortality, persistence, connection to wild nature |

| Theatre Masks | Tragic and comic faces | Transformation, performance, emotional range, catharsis |

| Bull | Powerful horned animal | Fertility, strength, sacrificial victim, sometimes Dionysus himself |

| Panther/Leopard | Wild big cat | Untamed nature, exotic origins, dangerous power controlled |

Key Myths Revealing Dionysus's Paradoxical Nature

Dionysus transforming pirates into dolphins, demonstrating his divine power and vengeance

The myths surrounding Dionysus reveal his complex, paradoxical nature – capable of bestowing great joy and abundance but also unleashing terrible punishment on those who denied his divinity or opposed his worship. These stories illustrate the fundamental duality at the heart of his character.

Dionysus and the Pirates: Divine Vengeance

One of the most famous myths tells how Dionysus was captured by Tyrrhenian pirates who failed to recognize his divinity. Taking him for a wealthy prince, they planned to sell him into slavery. Dionysus warned them, but they ignored him – until miraculous events began unfolding on their ship. Fragrant wine flowed across the deck, grapevines and ivy grew up the mast, and the god transformed into a roaring lion.

In terror, the pirates leaped overboard and were transformed into dolphins – a punishment, but also a kind of mercy, as dolphins were considered friends to sailors. Only the helmsman, who had recognized Dionysus’s divinity from the beginning, was spared. This tale demonstrates both Dionysus’s power to transform and his dual nature – capable of both terrible vengeance and unexpected mercy.

The Tragedy of King Pentheus: Resistance and Madness

Perhaps the most powerful story illustrating Dionysus’s dangerous side comes from Euripides’ tragedy The Bacchae. When Dionysus returned to his birthplace of Thebes, his cousin King Pentheus refused to acknowledge his divinity or permit his worship. Pentheus rejected the irrational, ecstatic elements that Dionysus represented, clinging rigidly to order and control.

In response, Dionysus drove the women of Thebes, including Pentheus’s mother Agave, into a Bacchic frenzy. They abandoned the city for the mountains, where they performed wild rituals. Dionysus then bewitched Pentheus, convincing him to disguise himself as a woman to spy on the Bacchantes. In their divinely-induced madness, the women saw Pentheus as a mountain lion and tore him limb from limb – with his own mother proudly carrying his severed head back to Thebes.

This brutal myth demonstrates the consequences of denying the Dionysian aspects of life – the irrational, emotional, and ecstatic experiences that are essential to human nature. By rejecting Dionysus, Pentheus ultimately fell victim to the very forces he sought to suppress.

King Midas and the Golden Touch: Blessing and Curse

Dionysus granting King Midas his fateful wish for the golden touch

In a more nuanced tale, Dionysus rewarded King Midas for his kindness to Silenus, the god’s elderly companion and teacher. When Silenus wandered away drunk and became lost, Midas found him and hospitably entertained him for ten days before returning him to Dionysus. Grateful for this kindness, Dionysus offered Midas any gift he desired.

Midas foolishly asked that everything he touched would turn to gold. At first delighted with his new power, Midas soon discovered its terrible consequences when his food, drink, and even his beloved daughter transformed into lifeless gold. Realizing his mistake, Midas begged Dionysus to release him from the “blessing.” Taking pity on him, Dionysus instructed Midas to wash in the river Pactolus, which carried away the golden touch and became known for its gold-flecked sands.

This myth illustrates Dionysus’s role as a giver of both blessings and curses, and the danger of desiring material wealth over life’s true pleasures – food, drink, and human connection – that fell within Dionysus’s domain.

Dionysus and Ariadne: Divine Love

Not all of Dionysus’s myths involve punishment. After the hero Theseus abandoned Princess Ariadne on the island of Naxos, Dionysus discovered her weeping on the shore. Struck by her beauty and moved by her suffering, he fell in love with her. Their wedding was a joyous occasion, and Dionysus later placed Ariadne’s crown among the stars as the constellation Corona Borealis.

This myth shows Dionysus’s capacity for compassion and love, transforming abandonment into divine marriage. It also connects him to the cycle of sorrow and joy that characterized his worship, as Ariadne’s grief gave way to celebration.

Ecstatic Worship: The Cult of Dionysus

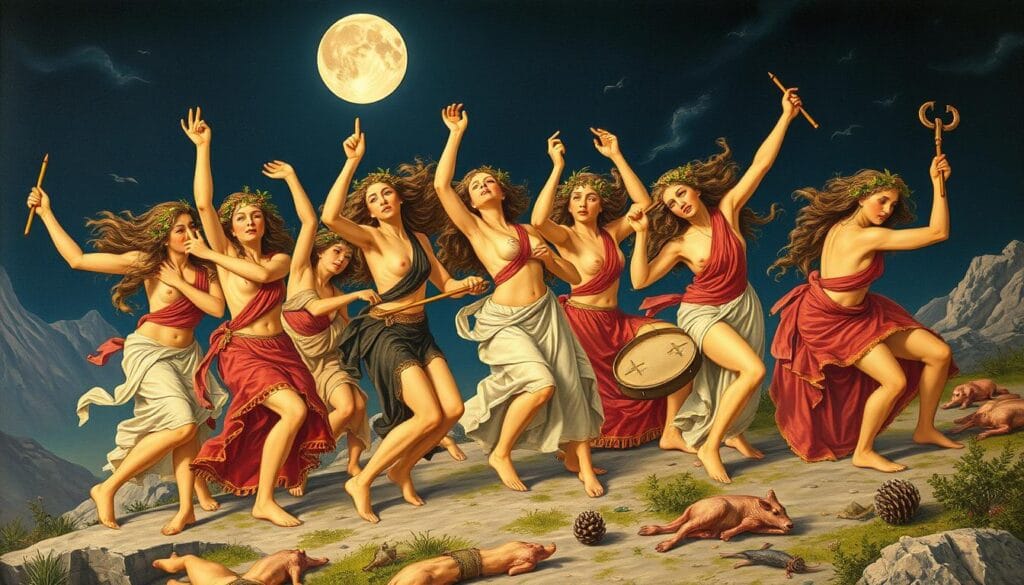

Maenads performing ecstatic rituals in worship of Dionysus

The Maenads: Women in Divine Frenzy

The most famous followers of Dionysus were the Maenads (also called Bacchantes or Thyiads), primarily women who abandoned their everyday roles to participate in ecstatic worship. Their name derives from the Greek word for “madness” or “frenzy,” reflecting their divinely-inspired state during rituals. Clad in fawn skins (nebris) and crowned with ivy wreaths, they roamed mountains and forests, dancing to the rhythm of drums and flutes.

In their Bacchic frenzy (oreibasia), Maenads were said to possess superhuman strength, tearing apart animals with their bare hands (sparagmos) and sometimes consuming the raw flesh (omophagia). While scholars debate how literally to take these accounts, the rituals clearly involved a dramatic departure from normal behavior and a temporary liberation from societal constraints.

For Greek women, typically confined to domestic roles, Dionysian worship offered a rare opportunity for religious expression outside male control. This aspect of his cult made Dionysus both popular among marginalized groups and threatening to established power structures.

The Dionysian Mysteries: Secret Initiations

Beyond public festivals, Dionysus was also worshipped through mystery cults that offered initiates a more personal, transformative religious experience. The Dionysian Mysteries involved secret rituals, symbols, and teachings that promised participants special knowledge and potentially a better fate after death.

These mysteries were connected to the Orphic tradition and the myth of Dionysus-Zagreus’s dismemberment and rebirth. Initiates may have symbolically reenacted this cycle of death and renewal, experiencing a form of ritual rebirth. The mysteries emphasized the divine element within humans and the possibility of achieving a blessed afterlife through proper ritual observance.

Unlike the public festivals, the mysteries were open to all social classes, including women, slaves, and foreigners. This inclusivity contributed to their popularity but also to suspicion from authorities, particularly in Rome where the Senate severely restricted Bacchic worship in 186 BCE.

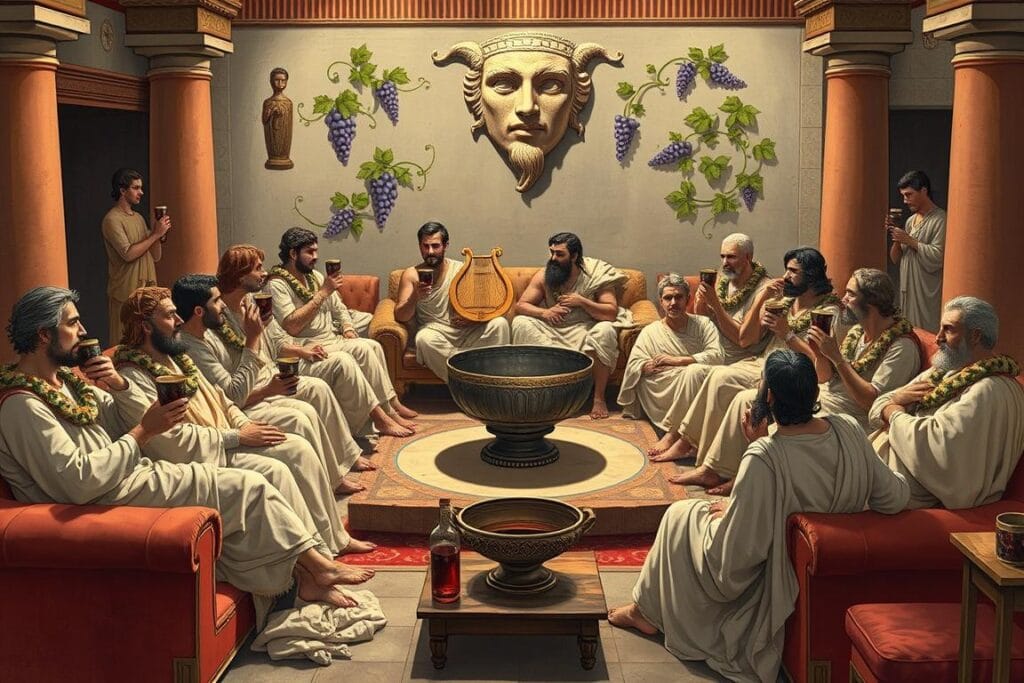

A Greek symposium with wine rituals honoring Dionysus

Wine Rituals and Symposia

Wine consumption played a central role in Dionysian worship, but it was carefully ritualized. The Greeks typically diluted wine with water in a large mixing bowl (krater) and followed specific customs for proper drinking. The symposium (drinking party) combined intellectual conversation with ritualized wine consumption, reflecting the Greek ideal of balancing Dionysian liberation with Apollonian restraint.

Before drinking, libations were poured to honor the gods, particularly Dionysus. The first crater was dedicated to the Olympian gods, the second to heroes, and the third specifically to Zeus Soter (Savior). A fourth crater marked the transition to less restrained celebration. This progression mirrored the Dionysian experience itself – moving from ordered ritual to more ecstatic states.

Wine was understood as a pharmakon – both medicine and poison – depending on how it was used. Proper consumption brought euphoria, creativity, and social bonding, while excess led to violence and destruction. This duality perfectly embodied Dionysus himself, capable of bestowing both blessing and madness.

From Ritual to Drama: Dionysian Festivals and the Birth of Theatre

Theatre performance at the ancient Theatre of Dionysus in Athens

One of Dionysus’s most profound cultural contributions was his association with theatre. The dramatic traditions that would shape Western literature emerged directly from festivals held in his honor, evolving from religious rituals to sophisticated artistic performances.

Major Dionysian Festivals

Several important festivals honored Dionysus throughout the Greek calendar, each with distinct characteristics:

- The Rural Dionysia – Held in December/January in villages throughout Attica, this festival celebrated Dionysus’s role in agriculture and featured processions carrying a wooden phallus symbol of fertility, improvised performances, and communal feasting.

- The Lenaia – A January/February festival focused on wine production, featuring comedy competitions and later adding tragedy performances. The name likely derives from lenoi (wine presses).

- The Anthesteria – A three-day February/March festival marking the opening of new wine. It included the Pithoigia (opening of wine jars), Choes (drinking competition), and Chytroi (offering to the dead), reflecting Dionysus’s connection to both celebration and the underworld.

- The City Dionysia – The most prestigious festival, held in March/April in Athens, featuring processions, sacrifices, and the famous dramatic competitions that produced the masterpieces of Greek tragedy and comedy.

From Dithyramb to Drama

Greek theatre evolved from the dithyramb – a choral hymn performed by 50 men or boys in honor of Dionysus. These performances initially recounted the god’s sufferings and triumphs, accompanied by flute music and dance. According to Aristotle, tragedy developed when a leader began separating from the chorus to take on character roles.

The poet Thespis (from whose name we get “thespian”) is traditionally credited with this innovation around 534 BCE. By adding a masked actor who could interact with the chorus, he created the basic dynamic of Greek drama. Later playwrights added more actors – Aeschylus introduced a second actor, and Sophocles a third – allowing for increasingly complex plots and character interactions.

Comedy similarly evolved from ritual processions (komoi) featuring ribald songs and improvised mockery, reflecting the uninhibited aspect of Dionysian celebration. By the 5th century BCE, both tragedy and comedy had developed into sophisticated art forms with established conventions, though they retained their religious connection to Dionysus.

Ancient Greek theatre masks representing tragedy and comedy, sacred to Dionysus

The Theatre of Dionysus

The physical space of Greek theatre itself honored Dionysus. The Theatre of Dionysus on the south slope of the Acropolis in Athens could seat approximately 17,000 spectators. At its center stood an altar to Dionysus, and his priest occupied the most honored seat. Before performances began, a sacrifice was made to the god, and his statue was carried into the theatre.

The theatrical experience itself had Dionysian qualities. Through the power of mimesis (imitation), actors temporarily transformed into other beings by donning masks – a quintessentially Dionysian act of metamorphosis. Audiences experienced emotional catharsis through witnessing the suffering of tragic heroes or the social critique of comedy, participating in a communal ritual that was both artistic and religious.

The plays themselves often explored Dionysian themes of transformation, the limits of human knowledge, and the tension between civilization and primal forces. Euripides’ The Bacchae, which directly depicts Dionysus and his worship, stands as a profound meditation on the god’s dual nature and the dangers of either embracing or rejecting his influence.

The Enduring Legacy of Dionysus

Modern expressions of Dionysian influence in wine culture, theatre, and festival celebrations

Nietzsche and the Dionysian Principle

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche revitalized interest in Dionysus through his influential work The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Nietzsche proposed a fundamental dichotomy in Greek culture between the Apollonian and Dionysian principles – Apollo representing order, reason, and individuation, while Dionysus embodied chaos, emotion, and the dissolution of boundaries.

For Nietzsche, the greatest Greek tragedies achieved their power by balancing these opposing forces. The Apollonian element provided form and narrative structure, while the Dionysian supplied emotional intensity and a connection to primal truths beyond rational understanding. He argued that modern Western culture had become overly Apollonian, suppressing the vital Dionysian energies necessary for artistic creativity and authentic living.

This concept profoundly influenced modern thought, particularly in psychology, aesthetics, and cultural criticism. The tension between Apollonian restraint and Dionysian release continues to provide a framework for understanding everything from artistic movements to social dynamics.

Psychological Interpretations

Building on Nietzsche’s ideas, psychologists have found in Dionysus a powerful archetype representing aspects of human psychology. Carl Jung saw Dionysus as embodying the Shadow – repressed instinctual energies that demand expression. The Dionysian experience offers a controlled encounter with these forces, preventing their destructive eruption through ritual channels.

Modern psychological interpretations view Dionysian rituals as serving important social and psychological functions. The temporary suspension of normal rules during festivals provided a safety valve for societal tensions, while ecstatic experiences offered individuals access to altered states of consciousness that could be psychologically regenerative.

Contemporary therapeutic approaches sometimes incorporate Dionysian elements, recognizing the healing potential in creative expression, emotional catharsis, and communal celebration. The god’s association with both suffering and joy reflects the psychological reality that transformation often requires passing through difficulty to reach renewal.

Modern wine festival celebrating traditions with roots in ancient Dionysian celebrations

Wine Culture and Modern Celebrations

The most obvious legacy of Dionysus persists in wine culture. Modern vineyard traditions, wine festivals, and tasting rituals echo ancient practices, though often without conscious mythological reference. The language used to describe wine – speaking of its “character,” “body,” and “spirit” – preserves something of the ancient understanding of wine as more than mere beverage.

Contemporary celebrations like Carnival, Mardi Gras, and certain music festivals contain distinctly Dionysian elements – the temporary suspension of normal social rules, costumes and masks that allow transformation, and the communal experience of music, dance, and intoxication. These events continue to fulfill the psychological and social functions that Dionysian festivals served in ancient Greece.

Even in more restrained form, the basic human needs that Dionysian worship addressed remain relevant: the desire for transcendent experience, release from everyday constraints, and connection to others through shared celebration. The enduring popularity of these experiences suggests that the Dionysian impulse remains a fundamental aspect of human nature.

Artistic and Theatrical Influence

Dionysus’s influence on the performing arts extends far beyond ancient Greece. Modern theatre, particularly experimental and immersive forms, often draws on Dionysian concepts of audience participation, emotional intensity, and boundary dissolution. Theatrical theorists like Antonin Artaud, with his “Theatre of Cruelty,” explicitly sought to recover the primal, transformative power of Dionysian performance.

In literature, the Dionysian archetype appears in characters who embody liberation, transformation, and the disruption of social norms – from Shakespeare’s Falstaff to more modern figures who challenge conventional boundaries. Visual artists continue to find inspiration in Dionysian themes of ecstasy, metamorphosis, and the tension between civilization and primal nature.

Perhaps most significantly, Dionysus’s legacy lives in our understanding of art itself as a transformative force that can alter consciousness and reveal truths beyond rational comprehension. The god who presided over the birth of Western theatre continues to symbolize art’s power to transform both creator and audience.

Embracing the Paradox: Dionysus in Modern Life

Symbolic representation of Dionysus’s dual nature – creative and destructive, ordered and chaotic

Dionysus remains one of the most relevant ancient deities for modern sensibilities. His paradoxical nature – simultaneously destructive and creative, foreign yet familiar, divine yet intimately connected to human experience – speaks to the complexities of contemporary life. In a world that often demands specialization and consistency, Dionysus reminds us of the value in embracing contradiction and the full spectrum of human experience.

The tension he embodied between civilization and primal nature continues to play out in our relationship with technology, social structures, and our own instinctual drives. His worship acknowledged that humans need both Apollonian order and Dionysian release – structure and spontaneity, reason and emotion, individuality and communal experience.

Perhaps most importantly, Dionysus represents the transformative potential in embracing life’s cycles of destruction and renewal. The god who died and was reborn teaches that transformation often requires a form of dissolution – the breaking down of old patterns to allow new growth. In personal development, artistic creation, and social change, this Dionysian principle of creative destruction remains powerfully relevant.

As we navigate an increasingly complex world, the ancient wisdom embodied in Dionysus offers valuable perspective: that joy and sorrow are intertwined, that true creativity emerges from embracing rather than denying our full nature, and that sometimes we must lose ourselves to find ourselves anew. The twice-born god of paradox continues to initiate us into these enduring mysteries.

Further Exploration: Dionysian Resources

Essential Books

- Dionysus: Myth and Cult by Walter F. Otto – Classic scholarly analysis of Dionysian religion

- The Birth of Tragedy by Friedrich Nietzsche – Philosophical exploration of Apollonian and Dionysian principles

- Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life by Carl Kerényi – Depth psychological approach to the god

Ancient Texts

- The Bacchae by Euripides – Tragic play directly featuring Dionysus and his worship

- Homeric Hymn to Dionysus – Early poetic treatment of the god’s myths

- Dionysiaca by Nonnus – Epic poem detailing Dionysus’s life and adventures

Modern Interpretations

- The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens by Pickard-Cambridge – Archaeological and historical study

- Dionysus Reborn by Henry Jeanmaire – Anthropological approach to Dionysian worship

- Ecstasy and the Praise of Folly by Daniel Rancour-Laferriere – Psychological analysis

Deepen Your Knowledge of Greek Mythology

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter for exclusive articles, recommended readings, and upcoming events exploring the rich world of Greek mythology and its modern relevance.

Visual Journey: Dionysus Through the Ages