Few figures in history have earned the title “Great,” but Alexander III of Macedonia undoubtedly deserves this distinction. In just 13 years of conquest, this military genius created one of the ancient world’s largest empires, stretching from Greece to northwestern India. His legacy transformed cultures, established new cities, and ushered in the Hellenistic Age that would influence civilizations for centuries to come. This article explores the remarkable life, military campaigns, and enduring impact of Alexander the Great, whose vision and ambition continue to fascinate historians and inspire leaders more than two millennia after his death.

Early Life and Education

Young Alexander receiving education from Aristotle, who greatly influenced his worldview

Born in 356 BCE in Pella, the capital of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia, Alexander was the son of King Philip II and Queen Olympias. His mother, a princess of Epirus, claimed descent from the Greek hero Achilles, while his father transformed Macedonia from a peripheral state into a formidable military power. From an early age, Alexander showed exceptional promise, displaying both intellectual curiosity and physical prowess.

At age 13, Philip appointed the renowned philosopher Aristotle to be Alexander’s tutor. For three years, Aristotle educated the young prince in medicine, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, and art. This education instilled in Alexander a deep appreciation for Greek culture and Homer’s works, particularly the Iliad, which he reportedly kept under his pillow alongside a dagger. Alexander especially admired the hero Achilles, whom he considered an ancestor through his mother’s lineage.

“I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a lion.”

— Alexander the Great

Alexander’s early military experience came at age 16 when Philip left him in charge of Macedonia while leading an expedition against Byzantium. During this time, Alexander quelled a rebellion by the Thracian Maedi, capturing their stronghold and renaming it Alexandropolis—the first of many cities he would name after himself. Two years later, he commanded the left wing at the decisive Battle of Chaeronea, where he personally led the charge that broke the Sacred Band of Thebes, an elite military unit.

Ascension to the Throne

In 336 BCE, Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard Pausanias during the wedding celebration of his daughter. At just 20 years old, Alexander quickly secured his position as king by eliminating potential rivals, including his cousin Amyntas IV and two Macedonian princes from the region of Lyncestis. He also brutally suppressed rebellions in Greece, most notably destroying Thebes when it revolted against Macedonian hegemony.

After consolidating power in Greece and securing the northern borders of his kingdom, Alexander turned his attention to his father’s unfulfilled ambition: the conquest of the Persian Empire. With approximately 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry, he crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor in 334 BCE, beginning one of history’s most remarkable military campaigns.

Military Campaigns of Alexander the Great

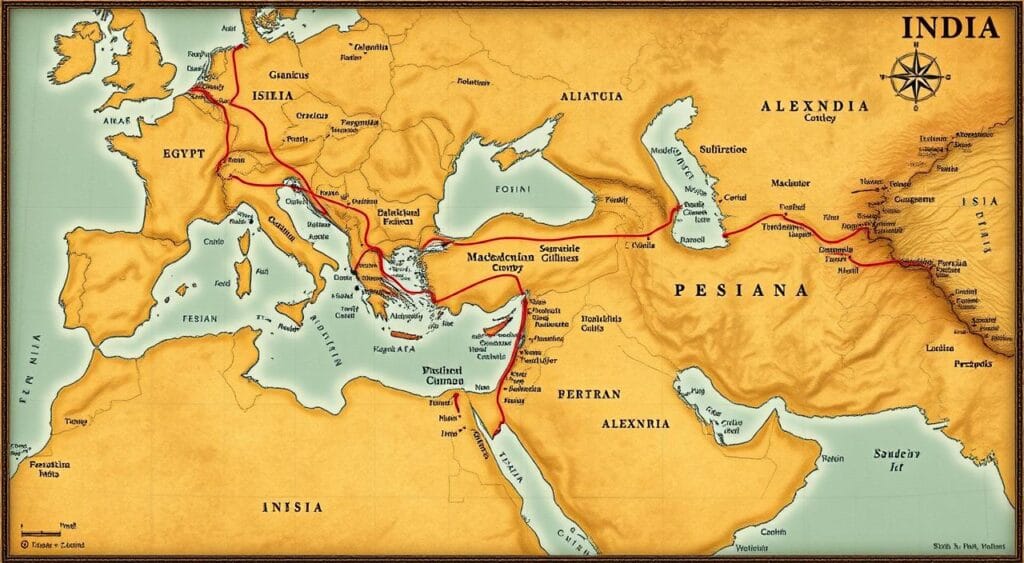

Map of Alexander’s conquests showing his route from Macedonia to India

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Alexander’s campaign against the Persian Empire began with a symbolic visit to Troy, where he paid homage to the Greek hero Achilles. His first major battle against Persian forces came at the Granicus River in 334 BCE, where he personally led a cavalry charge across the river against a force commanded by Persian satraps. Despite being outnumbered and nearly killed in combat, Alexander emerged victorious, securing western Asia Minor for his growing empire.

The Battle of Issus (333 BCE)

At Issus in southern Turkey, Alexander faced King Darius III and the main Persian army for the first time. Despite being vastly outnumbered, Alexander’s tactical genius prevailed. He personally led the Companion Cavalry in a decisive charge against the Persian left flank, creating a gap that allowed him to attack Darius directly. The Persian king fled the battlefield, abandoning his family who were subsequently captured by Alexander and treated with respect.

Following his victory at Issus, Alexander marched south along the Mediterranean coast, systematically reducing Persian strongholds. The siege of Tyre in 332 BCE demonstrated his determination and ingenuity. When the island city refused to surrender, Alexander constructed a causeway to reach its walls, developed specialized siege engines, and assembled a naval force to blockade the city. After seven months, Tyre fell, with Alexander ordering harsh punishment for the defenders.

Egypt and the Oracle of Ammon

After conquering Gaza, Alexander entered Egypt in 332 BCE, where he was welcomed as a liberator from Persian rule. The Egyptian priests at Memphis recognized him as pharaoh, granting him divine status. During his time in Egypt, Alexander founded Alexandria, which would become one of the ancient world’s greatest cities and a center of Hellenistic culture.

In a famous episode, Alexander journeyed across the desert to the oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis. What transpired there remains mysterious, but afterward, Alexander increasingly associated himself with divine status. Some historians suggest the priests confirmed his belief that he was the son of Zeus-Ammon, reinforcing his growing sense of divine mission.

Ruins of Alexandria, Egypt – one of many cities founded by Alexander the Great

The Heart of Persia

Returning from Egypt, Alexander led his army into Mesopotamia to confront Darius III once more. At the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BCE, he faced a Persian army that vastly outnumbered his forces on an open plain that favored Persian cavalry and chariots. Through brilliant tactical maneuvers, Alexander created a gap in the Persian lines and led his Companion Cavalry directly toward Darius, who fled the battlefield. This decisive victory effectively ended the Persian Empire.

Alexander proceeded to occupy the Persian capitals of Babylon, Susa, and Persepolis, acquiring immense treasures. At Persepolis, he allowed his troops to loot the city and later burned the royal palace, symbolically marking the end of the Persian Empire and completing the pan-Hellenic mission of revenge for Persia’s invasion of Greece 150 years earlier.

Alexander's Leadership Style

Alexander led from the front, personally engaging in combat and sharing hardships with his men. He was often first over city walls during sieges and sustained multiple serious wounds throughout his campaigns. This leadership style inspired intense loyalty among his troops, who followed him across thousands of miles of hostile territory.

Military Innovations

Alexander’s army utilized a combined-arms approach that integrated heavy infantry (the Macedonian phalanx), mobile cavalry, and specialized units like archers and javelin throwers. His military genius lay in his ability to adapt tactics to different terrains and opponents, from the set-piece battles against Persian armies to guerrilla warfare in mountainous regions.

Campaign into Central Asia

After the fall of the Persian Empire, Alexander pursued Darius into Central Asia. Though Darius was killed by one of his own generals, Bessus, Alexander continued eastward to secure the eastern provinces of the former Persian Empire. This campaign took him through modern-day Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia, where he faced fierce resistance from local tribes in difficult mountainous terrain.

During this period, Alexander adopted elements of Persian court customs and dress, attempting to rule as a Persian king as well as a Macedonian one. This cultural fusion policy created tension with his Macedonian veterans, culminating in the murder of Cleitus, one of Alexander’s close companions, during a drunken argument about these changes.

Invasion of India

Alexander facing King Porus and his war elephants at the Battle of the Hydaspes

In 327 BCE, Alexander led his army over the Hindu Kush mountains into the Indus Valley. His most significant battle in India came against King Porus at the Hydaspes River in 326 BCE. Here, Alexander faced a new challenge: war elephants. Through clever tactics, including a night crossing of the river to outflank Porus, Alexander secured victory. Impressed by Porus’s courage, he reinstated him as a vassal ruler.

Alexander wished to press further into India, but at the Hyphasis River (modern Beas), his army refused to continue. Exhausted by years of campaigning and monsoon rains, they demanded to return home. Reluctantly, Alexander agreed. Rather than retracing his steps, he led part of his forces down the Indus River while ordering a fleet constructed to explore the southern ocean. This journey through the Gedrosian Desert proved disastrous, with many soldiers dying from heat and thirst.

Discover Alexander's Military Genius

Want to learn more about the innovative battle tactics that allowed Alexander to defeat much larger armies? Explore our detailed analysis of his most famous victories.

Administration and Vision

Alexander’s empire was not merely a military conquest; he implemented administrative systems that would outlast his brief reign. In conquered territories, he often retained local governors who submitted to his authority, introducing a level of administrative continuity that facilitated governance of his vast domains.

Alexander adopting Persian royal attire as part of his cultural fusion policy

Cultural Fusion

One of Alexander’s most innovative policies was his attempt to blend Greek and Persian cultures. He encouraged intermarriage between his soldiers and local women, himself marrying the Bactrian princess Roxana and later Stateira, daughter of Darius III. At the mass wedding ceremony at Susa in 324 BCE, he arranged marriages between 10,000 of his soldiers and Persian women.

Alexander also incorporated Persians into his army and administration, adopting elements of Persian court ceremony and dress. This policy of cultural fusion, while visionary, created tension with his Macedonian veterans, who saw it as abandoning their traditions and privileged status.

City Founding

Alexander founded numerous cities throughout his empire, most named Alexandria. These urban centers became crucial for spreading Hellenistic culture and maintaining Greek influence long after his death. The most famous, Alexandria in Egypt, became one of the ancient world’s greatest cities and intellectual centers.

Economic Policies

Alexander established a unified currency system across his empire, facilitating trade and economic integration. He opened new trade routes between East and West and redistributed the vast Persian treasuries, stimulating economic activity throughout the conquered territories.

Scientific Endeavors

Alexander’s campaigns were accompanied by scientists, historians, and geographers who documented new lands, plants, and animals. This scientific exploration expanded Greek knowledge of the world and contributed to advancements in geography, botany, and zoology.

Religious and Divine Aspects

As his conquests expanded, Alexander increasingly associated himself with divinity. After visiting the oracle of Ammon in Egypt, he began to present himself as the son of Zeus-Ammon. In Persian territories, he adopted aspects of royal Persian religious practices, and in India, he showed interest in local philosophical traditions.

This religious syncretism reflected both political calculation and personal belief. By presenting himself in terms familiar to local religious traditions, Alexander facilitated acceptance of his rule among diverse populations while reinforcing his authority through divine association.

Death and Succession Crisis

Alexander on his deathbed in Babylon, surrounded by his generals

In June 323 BCE, while planning campaigns against Arabia and possibly Carthage, Alexander fell ill after attending a banquet in Babylon. After suffering from fever for several days, he died on June 10, 323 BCE, at the age of 32. The exact cause of his death remains debated, with theories ranging from malaria or typhoid fever to poisoning.

Alexander failed to name a successor, reportedly giving his signet ring to Perdiccas, one of his generals, when asked who should inherit his empire. When asked to whom he left his kingdom, he allegedly replied “to the strongest”—though this may be apocryphal. His death triggered an immediate succession crisis.

The Mystery of Alexander's Death

The circumstances surrounding Alexander’s death have fascinated historians for centuries. While the official explanation was that he died from illness, possibly malaria or typhoid fever, some ancient sources suggested poisoning. Modern medical historians have proposed alternative theories, including pancreatitis triggered by heavy alcohol consumption or complications from previous battle wounds. The mystery remains unsolved to this day.

In the aftermath of Alexander’s death, his generals—known as the Diadochi or “Successors”—fought for control of his empire. Despite the birth of Alexander’s son, Alexander IV, by Roxana shortly after his death, the empire quickly fragmented into separate kingdoms under different rulers. By 301 BCE, after the Battle of Ipsus, the empire had permanently split into several Hellenistic kingdoms, including the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in Persia and Mesopotamia, and the Antigonid Dynasty in Macedonia.

The Legacy of Alexander the Great

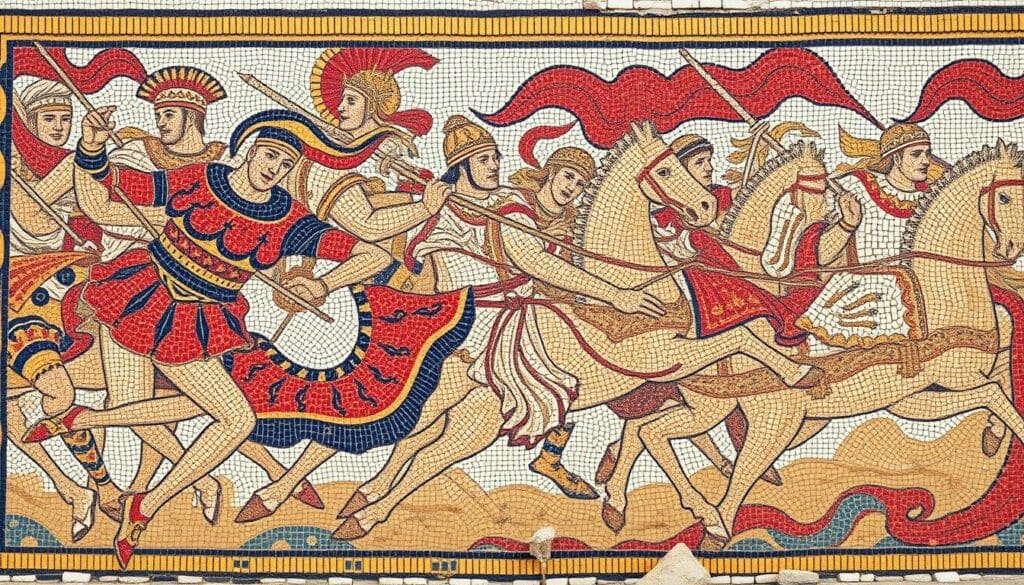

Famous Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii depicting the Battle of Issus

Cultural Impact: The Hellenistic World

Alexander’s most enduring legacy was the spread of Hellenistic culture across the vast territories he conquered. The period following his death, known as the Hellenistic Age (323-31 BCE), saw Greek language, art, architecture, literature, and philosophy flourish throughout the Mediterranean and Asia. Greek became the lingua franca of government, commerce, and culture across a vast region.

The cities Alexander founded became centers of Hellenistic civilization, with Alexandria in Egypt emerging as the intellectual capital of the ancient world. Its famous library and museum attracted scholars from across the known world, advancing fields from mathematics and astronomy to medicine and philosophy.

Artistic and Architectural Influence

Alexander’s conquests led to a fusion of Greek artistic styles with Eastern influences, creating distinctive Hellenistic art characterized by emotional intensity, realism, and dynamic movement. Architecture similarly evolved, with Greek elements appearing in buildings throughout the former Persian Empire, while Eastern motifs influenced developments in Greece itself.

Scientific and Philosophical Advancements

The Hellenistic period saw remarkable scientific achievements, including Eratosthenes’ calculation of Earth’s circumference, Archimedes’ mathematical and engineering innovations, and Euclid’s systematization of geometry. Philosophy diversified with new schools like Epicureanism and Stoicism addressing the challenges of living in a larger, more complex world.

Political and Military Legacy

Alexander revolutionized warfare through his combined-arms approach, tactical flexibility, and strategic vision. His military innovations influenced countless subsequent commanders, from Hannibal and Caesar to Napoleon and modern military theorists. The Hellenistic kingdoms that emerged from his empire developed sophisticated military systems based on his model.

Politically, Alexander’s empire demonstrated the possibility of governing diverse populations under a unified system. While his personal empire did not survive him, the concept of universal empire influenced subsequent rulers, including the Romans, who admired and emulated Alexander. The Roman Empire, in many ways, realized Alexander’s vision of a Mediterranean-centered world state.

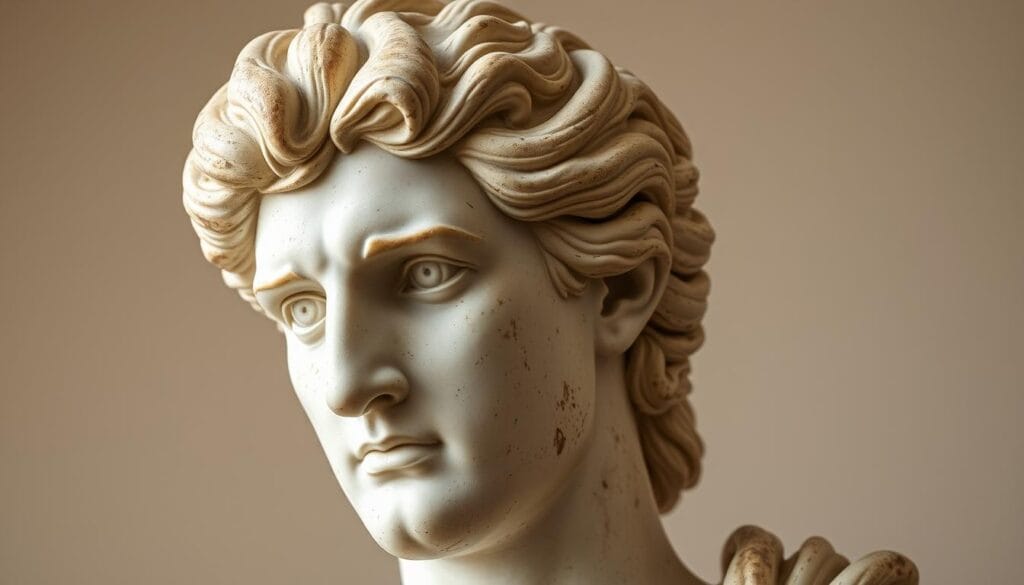

Roman marble bust of Alexander the Great, showing his characteristic features

Trade and Economic Impact

Alexander’s conquests connected distant regions, facilitating unprecedented commercial exchange between East and West. New trade routes opened, linking the Mediterranean with Central Asia and India. The circulation of vast Persian treasuries stimulated economic activity, while a common Greek-influenced culture facilitated business transactions across diverse regions.

The economic networks established during this period survived long after the political fragmentation of Alexander’s empire, creating enduring connections between Europe, Africa, and Asia that would influence the development of the Silk Road and later trade patterns.

Explore the Hellenistic World

Discover how Alexander’s conquests transformed culture, art, science, and philosophy across three continents in our comprehensive guide to the Hellenistic Age.

Alexander in Legend and Popular Culture

Few historical figures have generated as rich a legendary tradition as Alexander. The Alexander Romance, a collection of fantastic stories about his exploits, circulated widely in dozens of languages throughout the medieval period. In Persian and Islamic traditions, he appears as Iskandar, sometimes portrayed as a prophet or sage. These legends often attribute to him fantastic adventures, including journeys to the edges of the world and even underwater and aerial explorations.

In modern times, Alexander continues to fascinate, appearing in countless books, films, television series, and video games. His life has been interpreted through many lenses: as the embodiment of heroic leadership, as a ruthless conqueror, as a visionary unifier of cultures, or as a cautionary tale about the corrupting influence of power.

Medieval manuscript illustration from the Alexander Romance depicting one of his legendary adventures

Conclusion: The Measure of Greatness

Alexander the Great’s life and achievements continue to resonate across millennia, raising profound questions about leadership, ambition, cultural exchange, and the nature of greatness itself. In just 32 years of life and 13 years of rule, he created an empire spanning three continents, overthrew the world’s greatest power, founded cities that would flourish for centuries, and set in motion cultural exchanges that transformed the ancient world.

His legacy is complex and sometimes contradictory. The same man who ordered brutal massacres also showed remarkable cultural curiosity and respect for local traditions. The conqueror who subjugated millions also dreamed of a world united by common culture and commerce. The military genius who never lost a battle ultimately could not secure his succession or ensure his empire’s survival.

Perhaps Alexander’s true greatness lies not in the territory he conquered—which quickly fragmented after his death—but in the cultural synthesis he initiated. The Hellenistic civilization that emerged from his conquests created a shared intellectual and artistic heritage that would influence the Roman Empire and, through it, the development of Western civilization, while simultaneously preserving and transmitting elements of Persian, Egyptian, and Indian cultures.

More than two thousand years after his death, Alexander the Great remains the standard against which military leaders and empire-builders measure themselves—a testament to his enduring impact on history and the human imagination.

“There is nothing impossible to him who will try.”

— Alexander the Great

Continue Your Historical Journey

Fascinated by Alexander the Great? Explore our collection of in-depth articles on ancient history’s most influential figures and empires.

Frequently Asked Questions About Alexander the Great

How did Alexander the Great die?

Alexander died in Babylon on June 10, 323 BCE, at the age of 32. The exact cause of his death remains debated among historians. The most common theories include malaria, typhoid fever, or other infectious diseases. Some ancient sources suggested poisoning, while modern researchers have proposed other possibilities including pancreatitis (possibly related to heavy alcohol consumption) or complications from previous battle wounds. He fell ill after attending a banquet and suffered from fever for about ten days before his death.

Why is Alexander called “the Great”?

Alexander earned the epithet “the Great” due to his extraordinary military achievements, the vast empire he created, and his lasting cultural impact. He never lost a battle, conquered the Persian Empire (the superpower of his day), and created an empire stretching from Greece to northwestern India. His conquests spread Hellenistic culture across a vast area, influencing art, architecture, language, and thought for centuries. The title “Great” was not used during his lifetime but was applied by later generations in recognition of his historical significance.

What was the Gordian Knot, and why is it associated with Alexander?

The Gordian Knot was an intricate knot used to secure an ancient wagon at Gordium in Phrygia (modern Turkey). According to legend, an oracle had declared that whoever could untie this impossibly complex knot would become the ruler of Asia. When Alexander encountered the knot in 333 BCE, he allegedly solved the problem by slicing through it with his sword rather than trying to untie it—creating the expression “cutting the Gordian knot” to describe solving a complex problem through bold, decisive action. This story, whether historical or legendary, symbolizes Alexander’s decisive character and refusal to accept conventional limitations.

Did Alexander the Great really tame the horse Bucephalus?

According to historical accounts, particularly Plutarch’s Life of Alexander, the young Alexander (around age 12 or 13) did indeed tame the horse Bucephalus when no one else could approach it. Alexander noticed the horse was afraid of its own shadow and turned it toward the sun before mounting it. This impressed his father, Philip II, who reportedly said, “My son, seek out a kingdom worthy of yourself, for Macedonia is too small for you.” Bucephalus became Alexander’s faithful war horse for nearly 20 years, carrying him through numerous battles until its death in India in 326 BCE.